ULO1: Interpret relevant data and design research insights to provide a rationale for design decisions.

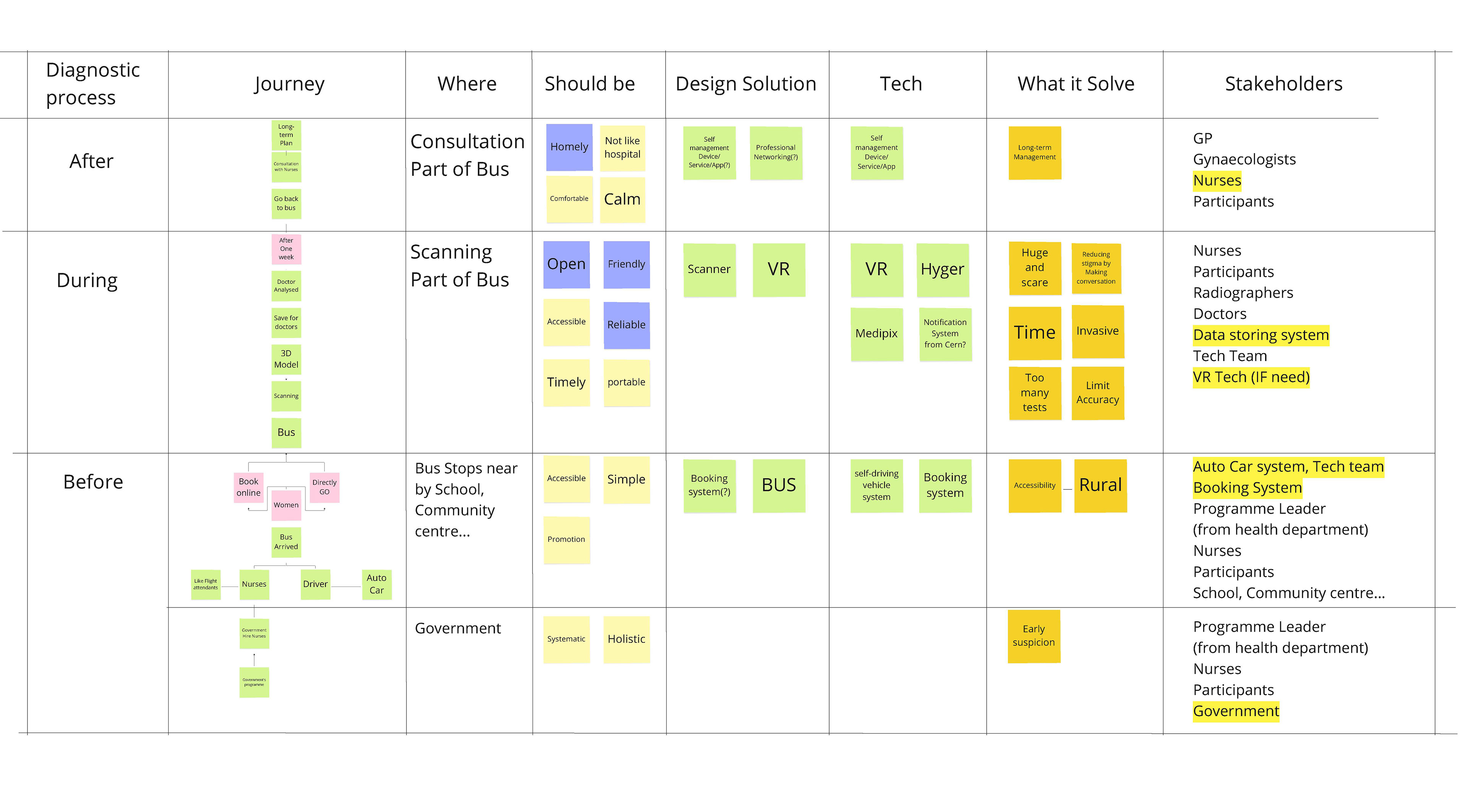

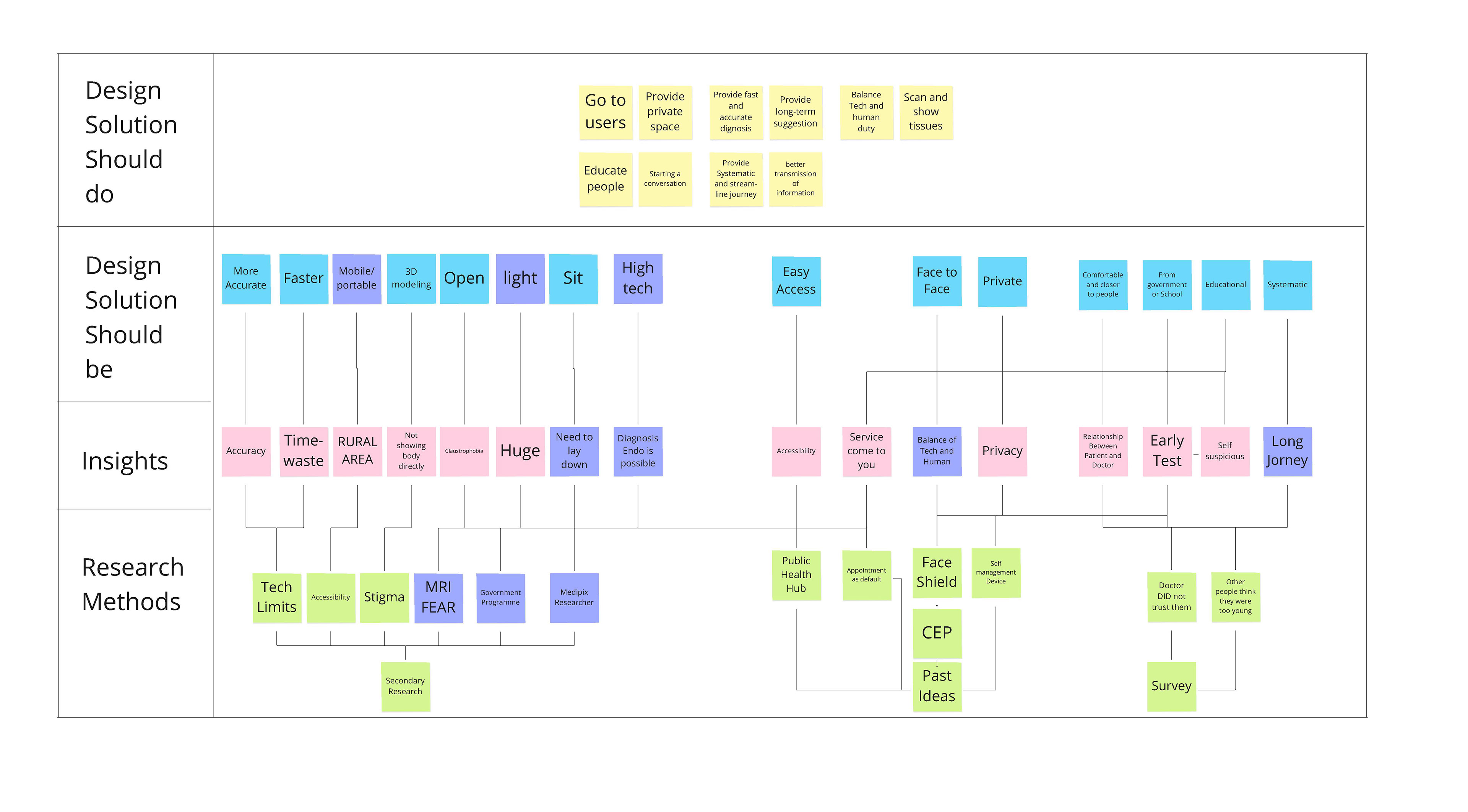

At the end of CBI-A³ Phase One, We identified three main reasons women might experience the delayed diagnosis of endometriosis: stigma, limited accessibility, and technological limitations.

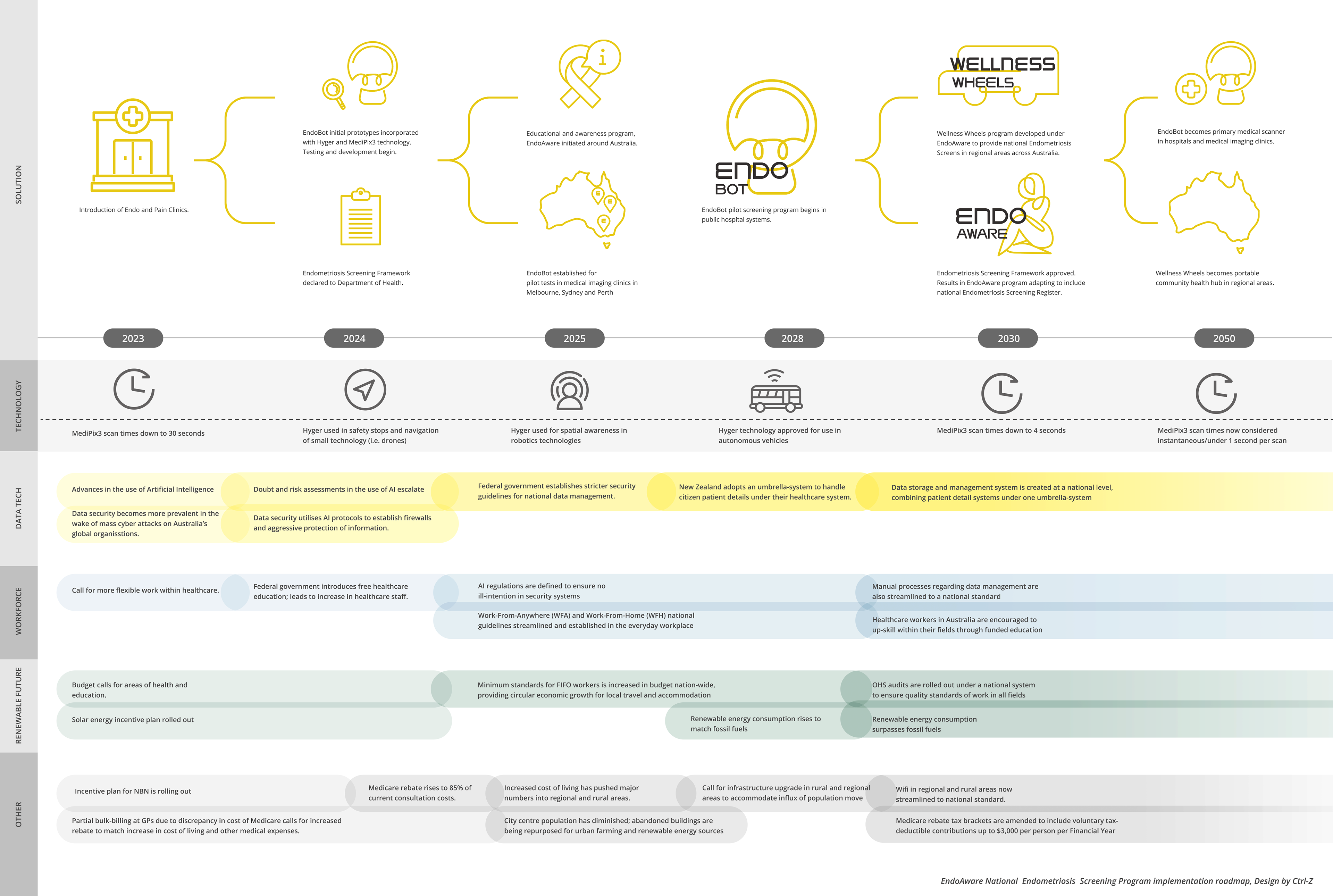

To address this issue, we considered prototyping as a design method at the beginning of the second phase, creating diegetic prototypes for a 2050 scenario with a public health hub supporting early detection for women.

Our diegetic prototypes included a journey map and storyboard to collect the data through online text interviews. By the Affinity map, we understood that most agreed that the public health hub could be a viable option by 2030-2050 but expressed concerns about funding and the system.

As a result, we researched the national screening test and sex education program to seek funding from the government. Therefore, we discovered that the Australian sexual education program is based on buses around different schools as well as “Early cancer detection and Screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People” program is also operated by buses or trucks. Our solutions were significantly impacted during this stage as we transitioned the public health hub to a national screening test program that utilised a bus.

When applying the concept of Planet Centric Design, we realised that human resources were a crucial factor in our solution. During the behaviour change section, we identified that the system of flight attendants could be adapted to the EndoAware system. The nurses will travel across Australia through Wellness Wheels, with appropriate local accommodation plans.

In addition, by researching future trends for 2030, we incorporated possible technologies and environments into our solutions. For example, we included the Wellness Wheels bus with a self-driving system and powered it with solar energy.

ULO2: Critique theories underpinning various design innovation practices.

During the CBI-A³ program, the team utilised prototyping as a design method multiple times. Prototyping allows for effective communication amongst team members during different project stages and aids in testing and translating the prototype at various levels. This method helps to prevent misunderstandings and ensure that each team member's ideas are accurately conveyed (Kocsis et al., 2017). Introducing diegetic prototypes provided a new perspective by creating a cinematic context without directly linking it to our existing solution. This approach allows designers to explore "what if" or "what can it be" scenarios in the service design innovation field (Harwood et al., 2019). In addition, diegetic prototypes are often used to showcase future scenarios to the public. Undoubtedly, prototyping diegetic prototype is an efficient way to practice prototyping and user testing.

Moreover, it helped us discover a new idea we did not gain before. On the other hand, I wonder if diegetic prototypes can be a practice experience for prototyping and a method to generate ideas for tangible solutions. This section ended with the 2050 prototype analyses, but bringing 2050 back to 2030 is another challenge. If we can create ideas and utilise the feedback from diegetic prototypes and our 2050 future scenario at the end of this session, we could connect 2050 and 2030 more directly and have more future thinking ideas.

Besides, it was a little bit ambiguous to define the differences between 2050 and 2030, this caused us to come up with the public health hub in this session, but it was also adapted for 2030 directly. In conclusion, diegetic prototypes are beneficial for setting the atmosphere for the audience and helpful for practising different types of prototypes. Nevertheless, when there are two different future sets, it would be challenging to define the difference and influence between each other.

Design is a complex and elusive concept that has taken on various interpretations throughout history, making it difficult to provide a straightforward definition (Rawsthorn, 2015). Behaviour change (behaviour design) is a significant factor in innovation design, but psychology is a complex area for most designers. It was a balance between theory and practice in this section.

As J & Linsey et al. (2008) show, analogies and metaphors are essential in creative design, enabling the transfer of knowledge and generating unique solutions. Therefore, the “Design with Intent” toolkit is a valuable method for enhancing the imagination of participants. As Heise (2019) said, “Creativity is like a muscle – it needs to be flexed regularly if it’s to play a positive role in your life.”. Suppose we train ourselves to regularly discover the mechanism or system behind our daily life. Then, we can transfer them to benefit our solution area.

For the behaviour design section, I would like to know if participants can prototype and test their ideas for behaviour change. In this way, it would be an excellent opportunity to observe whether people change their behaviour and which theory be applied.

Critical Experience Prototyping (CEP) is a design method that centres around designing and prototyping experiential scenarios rather than focusing solely on the product. It enables designers to illustrate a product or service's functionality in a context that users can understand and relate to. In our case, we used CEP to develop and refine the Anonymous Mask crowd anonymity device.

However, a critique that can be drawn from this process is that CEP's effectiveness may depend significantly on the clarity of its implementation and the project's scope. For example, in our case, the initial prototype failed to capture the actual shape and form that the final product required, which led to a disconnection between the prototype and users' perceptions.

This indicates that while CEP can be a powerful tool for empathising with users and creating more user-centred designs, it should be used cautiously. Its implementation should always consider the complexity of the issue it aims to address. Furthermore, the prototype should simulate the product's function and challenge and potentially change the existing mindset towards the subject.

ULO3: Create prototypes that are relevant to various stages of the innovation process.

My contributions were instrumental in driving the progress of two prototypes. One of them was the diegetic prototype, as the foreword mentioned. For creating the cinematic scenario for the audience and practising the ability of prototyping, we came up with the public health hub for supporting the setting of “health in public”. For me, the purpose of diegetic prototype in that stage could be communication with team members to ensure we were in the same future context, exploring new ideas through 2050 future scenarios and practising how to test/ gain feedback from users.

For example, I did the storyboard to present this public health hub to users. Storyboarding, while a straightforward method, was not frequently employed during our work in the CBI-A³ program. Despite its limited use, the storyboard became an invaluable tool during online interviews due to testing time constraints. During my user testing, I found that using this medium efficiently describes context and scenarios to participants. This process gave me valuable insights, including funding and data security concerns.

Roselló (2017) suggests that diegetic prototypes, a component of the design fiction methodology, enable us to prototype tangible objects that inherently carry narrative properties. These objects serve as time-travel devices, allowing us to explore future scenarios and ponder the kind of tomorrow we desire. Contrarily, Harwood et al. (2019) propose that storyboards can be incorporated into the design fiction process as visual aids to illustrate service innovations. Visual storytelling via storyboards can bring innovative ideas to life, making them more understandable and tangible for all involved.

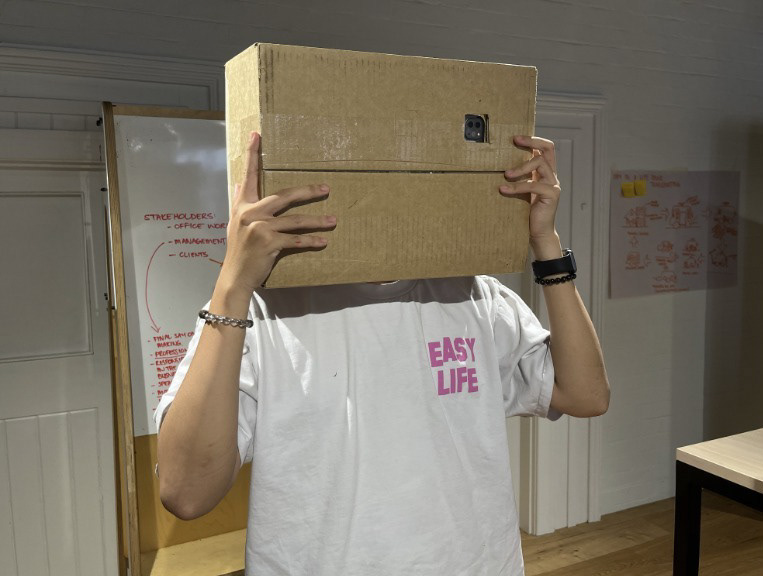

Another prototype in which I was heavily involved was the Critical Experience Prototype (CEP). We developed the Anonymous Mask crowd anonymity device to reduce the stigma and improve privacy. In this case, the prototype was the tangible object to communicate with team members who did not participate in the ideation session, the efficient tool to validate our hypotrophy whether on the right track and the straightforward way to refine the shape and system through user testing and feedback.

For example, I made two versions of this Anonymous Mask crowd anonymity device. And both of them should focus on two aspects. The first was how the user felt about the shape or appearance of the device, and the second was how the user felt about the anonymous system when they wore the device (function and inner feeling).

I made a low-resolution prototype made of cardboard and an iPad in class. It was not a rational prototype for testing the shape. The cardboard was not fit the head, and people related with robots or related contexts. Relevantly, this CEP showed the device's function excellently through an iPad Instagram filter.

The quality of the second CEP for this Anonymous Mask crowd anonymity device was higher than the first. We changed its shape to a face shield because of the feedback from the first CEP. In addition, I made three blur mode videos to understand how the user feels using this device. Unfortunately, from the test and feedback, we know this device improved the patient and doctor’s privacy, but it built another massive gap between patient and medical practitioner. I remembered that one feedback I gained was that “ you want to reduce the stigma and improve the relationship between patient and doctors, but the anonymous system was a device that help people hide and escape; it did not solve the problem from the root.” On the other hand, some opportunities and positive feedback, such as users liking the avatar (Mario) mode. They thought it helped children feel more comfortable in the hospital.

ULO4: Formulate visualisations and storytelling narrative to communicate the value and intent of a design solution.

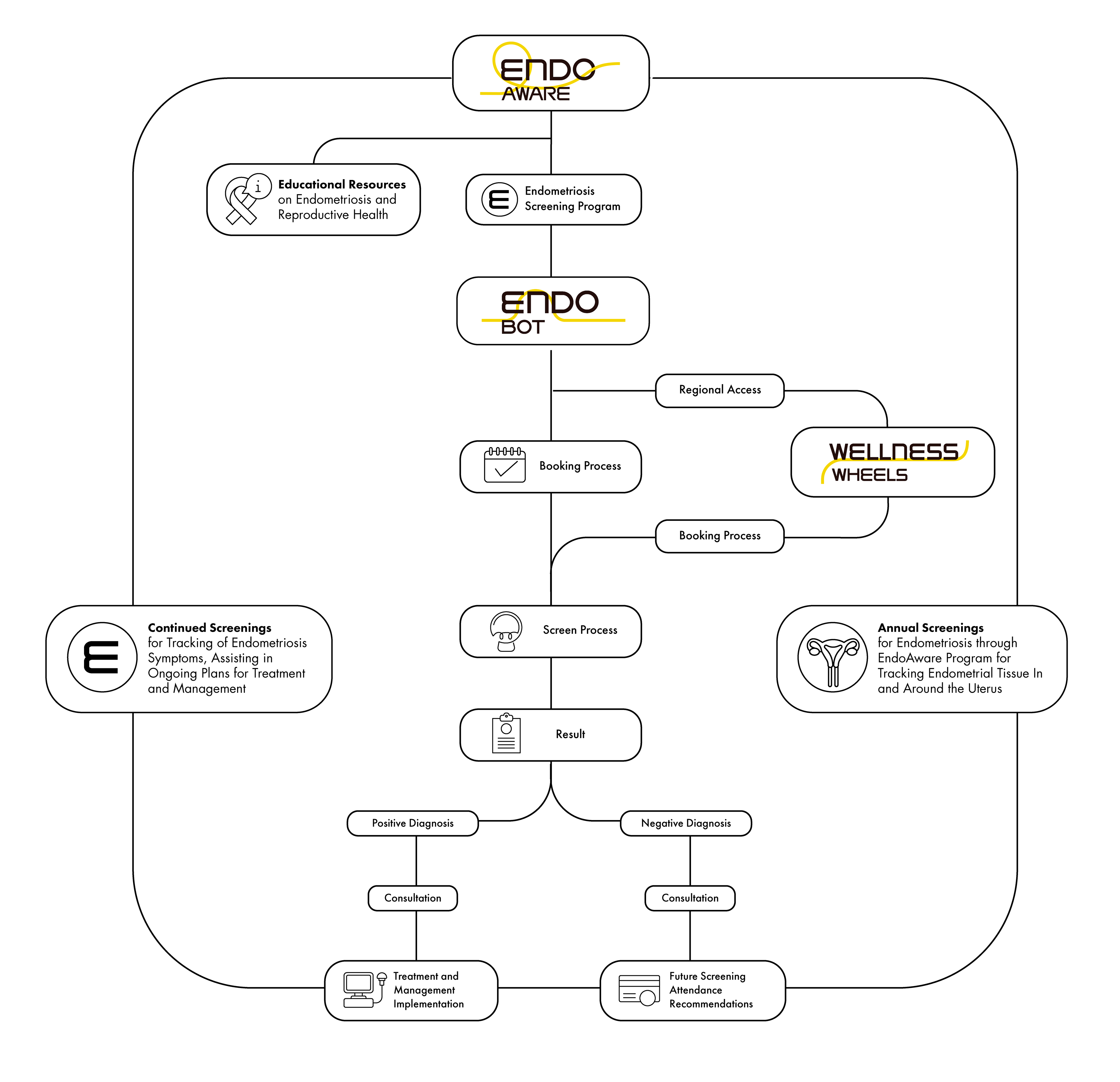

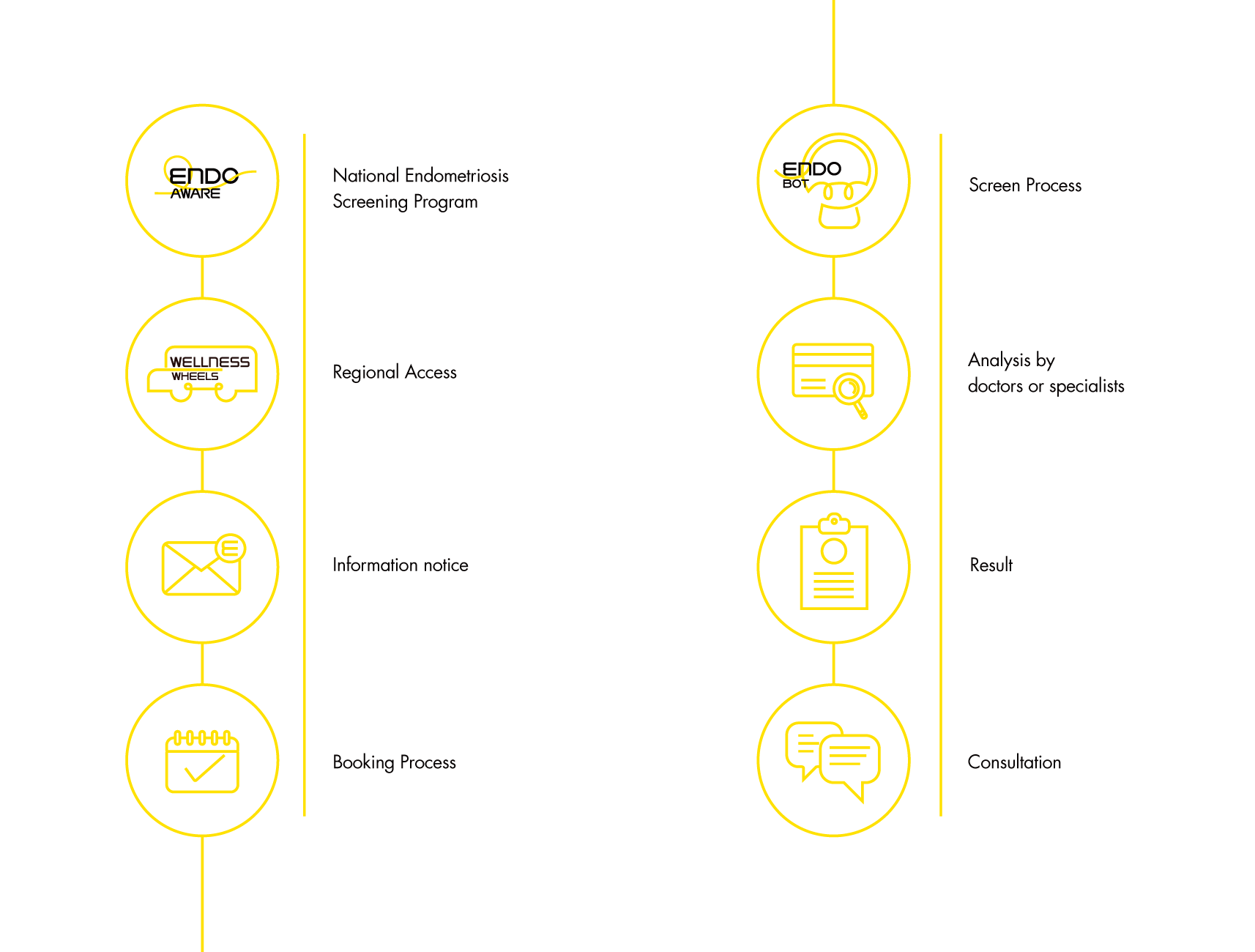

As a communication designer for the CBI-A³ program, I was responsible for creating visual communication designs using effective strategies, such as developing brands for our solutions, creating a visual roadmap for implementation, and designing solution videos. One example was the EndoAware branding system, which included three related brands - EndoBot, Wellness Wheels, and EndoAware. Our team was inspired by the yellow ribbon symbol for endometriosis awareness, but designing a logo with such a direct symbol was a challenge. I ultimately decided to use a yellow line as our branding key element, inspired by the yellow ribbon but developed differently.

EndoAware is a National Screening Program, so it needed to convey professionalism, reliability, and friendliness and be positive, welcoming, and inspiring as a campaign.

Designing the solution video was complex; I followed the script and created different footage to match the vocals. It was challenging to determine the appropriate length of each scene and how many times they should be repeated to maintain the audience's attention.

ULO5: Develop holistic design solutions covering technical, economic and human considerations in response to complex project briefs.

One of our solutions, EndoBot, is a new diagnostic tool that uses advanced technology to provide a non-invasive and accurate method for diagnosing endometriosis. With Medipix and Hyger, we can create a 3D colour image of the body that can identify endometrial tissue in the pelvic cavity that other imaging methods may miss. Hyger technology also ensures that the images produced are precise by adjusting to any micro-movements made by the patient during the scan. This is a significant improvement over traditional diagnostic methods, which can be invasive and less accurate.

EndoAware is aligned with the Australian government's 2022-23 budget, which has allocated $58.3 million for addressing endometriosis and pelvic pain. This funding will support the implementation of our national screening program, EndoAware, which is modelled after existing screening programs for conditions like breast and cervical cancer. We believe this program will lead to cost efficiencies by leveraging established infrastructure and processes. Additionally, our transportable consulting rooms, called Wellness Wheels, will make healthcare more accessible to those in regional and rural areas, reducing costs associated with travel and hospital stays.

EndoAware program aims to provide endometriosis screening for Australians and educate them about reproductive health and endometriosis. EndoAware program could also alleviate the stress and uncertainty associated with the diagnostic process by quickening the diagnosis journey for women with endometriosis. Wellness Wheels further address human needs by making the program accessible to those living in regional and rural areas, providing these communities with access to advanced diagnostic technology and creating an opportunity for education and awareness about reproductive health.

In conclusion, EndoAware Program is a holistic design solution that addresses the technical, economic, and human aspects of diagnosing endometriosis. By leveraging advanced technology, aligning with government funding, and focusing on human needs, the solution presents a comprehensive and thoughtful approach to a complex problem.

ULO6: Support conditions for innovation culture as a team member through inclusive project management, empathy and open-mindset. ULO7: Conduct techniques relevant to coaching design innovation activities.

The 6.5-month innovation program with a multidisciplinary and diverse team was a considerable challenge for me. Our morale hit a significant low during the program's midpoint, specifically from the end of Phase 1 to the beginning of Phase 2. We faced numerous obstacles, from personal issues like family emergencies, illness and accidents, and relationship strains to project-related problems. In addition, our position at the midpoint of the design project coincided with a dip in enthusiasm post our trip to Switzerland, and the expectations for the project were also relatively low. This situation made finding motivation and supporting the team towards the program's end, particularly challenging.

Due to these internal and external factors, team members were absent during critical stages from Diegetic Prototyping to Critical Experience Prototyping. As a result, there were numerous instances where it was just me and another random member, or in the worst-case scenario, just me doing ideation, attending meetings, or working on prototyping.

Understanding the complexities and dynamics of teamwork, I did not assign blame to any individual. Instead, I strived to maximise my contributions, particularly in my role as the member responsible for documenting and communicating the content of each process. For example, during the Critical Experience Prototyping phase, when I was almost the sole member present, I took on the task of organising the class content and documents diligently. I created a comprehensive Google document and used our group communication channel to inform my team members about tasks and schedules. This proactive approach sparked responses from different team members who, in turn, helped test the prototype.

Recognising that this was a marathon and not a sprint, I understood that each member could face low morale, personal issues, and discomfort at various times. During these periods, I focused on maintaining a positive and open mindset and sustaining my confidence in the team's capabilities and potential.

Indeed, all team members returned for the Planet Centric Design session, and they brought encouraging news about our dialogue with Medipix technology experts to advance our solution. The team members regained their vigour and enthusiasm following this development, propelling us towards the final proposal with renewed energy and optimism.

Although I was not a designated leader in this program, and I couldn't assist with the personal issues of the team members, my mindset was focused on doing what I could and maintaining my faith in the team. My commitment to inclusive project management, empathy, and an open mindset proved instrumental in fostering a supportive and innovative environment. My experiences in this program underscored the importance of these values in ensuring the conditions for innovation in a team setting. As I reflect on this journey, I realise that these experiences have not only enriched my understanding of teamwork and project management but also affirmed my belief in the power of resilience, inclusivity, and open communication in overcoming challenges and fostering innovation.

Reference

Harwood, T., Garry, T., & Belk, R. (2019). Design fiction diegetic prototyping: a research framework for visualizing service innovations. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsm-11-2018-0339

Heise, A. (2019, November 25). Making a habit of creativity. Law Society Journal. https://lsj.com.au/articles/making-a-habit-of-creativity/

Hey, J., Linsey, J., Agogino, A., & Wood, K. (2008). Analogies and metaphors in creative design. International Journal of Engineering Education. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Analogies-and-metaphors-in-creative-design-Hey-Linsey/fa150a5c1578ffa2b1ae8172892a3b3929e96224

Rawsthorn, A. (2015, June 10). What is design? Www.youtube.com. https://youtu.be/vIBQEeH14ks

Roselló, E. (2017, June 14). Design Fiction: Prototyping Desirable Futures. CCCB LAB. https://lab.cccb.org/en/design-fiction-prototyping-desirable-futures/